Bangladesh to vote tomorrow: What’s at stake for India, Pakistan and China – The Times of India

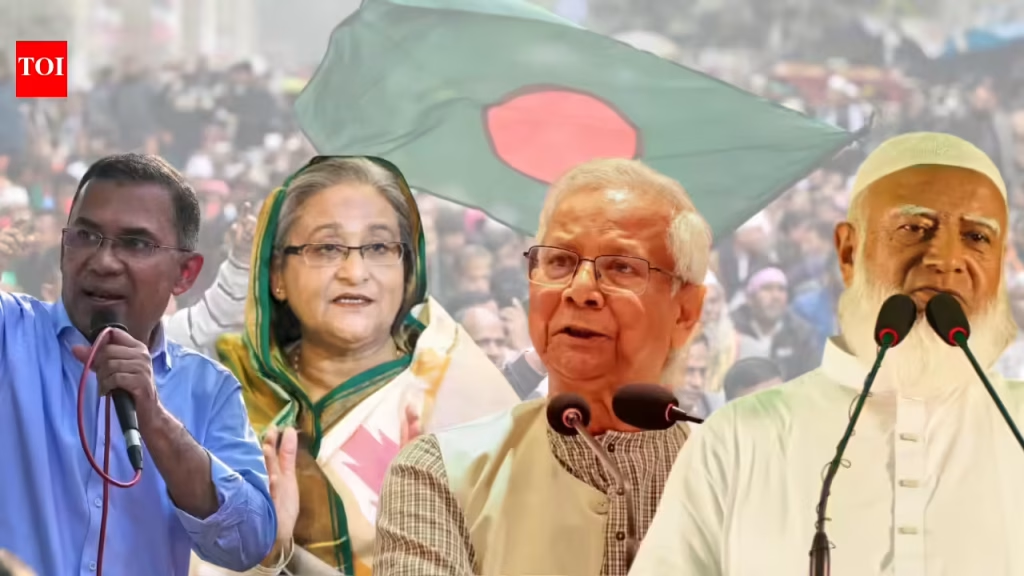

After months of violence, street protests and political upheaval, Bangladesh now faces its moment of reckoning. What began in July 2024 as a student agitation over public sector job quotas quickly spiralled into a nationwide revolt against Sheikh Hasina’s government, culminating in her resignation and flight to India. The unrest left more than 1,000 people dead and dismantled a political order that was entrenched in Dhaka’s politics for over a decade.Now, on February 12, Bangladesh votes in its first general election since that uprising, a ballot that will test not only the strength of its democracy but the direction of its national identity. Nobel laureate Muhammad Yunus who took charge after Hasina’s ouster said that the interim government “will hand over the responsibility to the newly elected government with deep pleasure and pride.”But the field has been radically reshaped. The once-dominant Awami League has been sidelined, opening the field to a resurgent Bangladesh Nationalist Party under Tarique Rahman and an emboldened Jamaat-e-Islami seeking renewed legitimacy.For Bangladesh, this is a struggle to restore stability after a stint with instability. But it also holds a significant impact on a region that has battled with growing instability, where governments have fallen and leaders have fled faster than Pakistan’s military has overturned governments.For India, China and Pakistan, it is a moment that could redraw the strategic balance in South Asia.

How we got here

In 2024 widespread student protests erupted over public sector job quotas, but quickly escalated into a nationwide revolt against the Hasina government. By early July, protesters clashed violently with police in Dhaka and other cities. The unrest peaked in early August when security forces opened fire on demonstrators. On 5 August 2024 the situation culminated in the resignation of Sheikh Hasina, who immediately left for India. Over 1,000 people were killed in the clashes – the deadliest violence Bangladesh has seen since its 1971 independence war.

In the aftermath, a caretaker government was formed, headed by Nobel laureate Prof. Muhammad Yunus (best known for microfinance). This interim cabinet – comprising ex-bureaucrats, civil society figures and student leaders – took power in late August 2024. It promised to uphold order, prosecute crimes committed during the protests, and prepare for new elections. One of its first actions was to promulgate a provisional “July Charter” of reforms, advocating constitutional changes and term limits to curb executive power. A referendum on this charter is also being held alongside the election.By law the elections must be held by early 2026. Notably, the once-dominant Awami League (AL) was effectively excluded: the interim government has banned the AL in response to allegations of crimes during the protests. Instead, the race centers on the BNP-led opposition coalition (with Islamist allies) and several smaller groups including a new National Citizen Party (NCP) founded by student activists. Professor Harsh V. Pant, Vice President at the Observer Research Foundation, believes Bangladesh’s election is unlikely to produce a sharp geopolitical pivot. Instead, he argues, pragmatism will prevail.“But the most likely outcome is that whoever comes to power in Bangladesh is likely to be pragmatic in its engagement with both India and China,” Pant told The Times of India. In his assessment, it would be “very foolhardy of any government in Dhaka to take a one-sided view of the India–China relationship or to tilt to one side or the other”.Pant stressed that balancing both Asian powers is not merely diplomatic caution but strategic necessity. “It helps Bangladesh if they are engaged with both India and China,” he said, adding that such engagement allows both countries to “help Bangladesh shore up its capabilities”.

Which are the key parties?

A BNP under new leadershipThe Bangladesh Nationalist Party (BNP) has been one of the two major parties in Bangladesh for decades. Founded by President Ziaur Rahman in the late 1970s, it has been led by his widow, Khaleda Zia, since 1984. Khaleda served three terms as prime minister (1991–96, 2001–06) and was a central figure in Bangladeshi politics.

Khaleda Zia’s influence was immense, and even after years of legal troubles and house arrest in the late 2010s, she remained BNP’s unchallenged leader. Her death in late December 2025 has now left a leadership vacuum. The party immediately chose her eldest son, Tarique Rahman, as acting chairman. Tarique had fled the country in 2007 amid corruption charges, and for nearly 18 years lived in exile in London. His surprise return on 25 December 2025 was a dramatic moment: thousands of BNP supporters greeted him, and he has positioned himself as the torchbearer of his mother’s political legacy. BNP sources say Tarique will formally assume party leadership to guide the BNP into the poll.Tarique Rahman’s re-entry greatly energised the BNP base. He is widely expected to be the party’s prime ministerial candidate if the alliance wins a majority. In his very first campaign speeches, Tarique struck themes of national pride and stability: he criticized Islamist rivals for exploiting religion, and vowed to “uphold national sovereignty and work for women and young people”. Supporters wearing BNP’s yellow and green flocked to see him, chanting slogans of independence and democratic change.

The BNP’s weaknesses have also become apparent. Khaleda’s long illness had largely kept her out of politics since 2018, and the party’s cadres have suffered under AL crackdowns in recent years. Its alliance building is fragile: Jamaat-e-Islami (to be discussed below) is a key ally, but other Islamist groups have even broken away from Jamaat’s alliance over seat disputes. Nonetheless, with the AL absent, Tarique’s return has put BNP in the front seat for power. Indian officials have already moved to engage with the new BNP leadership: at Khaleda’s December funeral, EAM Jaishankar delivered PM Modi’s condolence letter to Tarique and “expressed optimism about strengthening bilateral relations following Bangladesh’s democratic transition”.

Jamaat-e-Islami’s resurgence

Jamaat-e-Islami (JeI) is Bangladesh’s largest Islamist party. It was banned from elections and effectively outlawed after 2013, when courts ruled its charter violated the secular constitution. Many Jamaat leaders had been convicted for war crimes in the 1971 Liberation War, due to the party’s support for Pakistan during that conflict. For over a decade under Awami League rule, the Jamaat was excluded from politics.That changed in mid-2025. On June 1, 2025, Bangladesh’s Supreme Court restored Jamaat’s registration. This landmark decision came as the interim government promised inclusive polls. The court lifted Jamaat’s election ban and overturned the conviction of one of its leaders, paving the way for its participation in the 2026 elections. Legal observers said the ruling allowed a “more democratic, inclusive and multiparty system”. With Jamaat back in play, the Islamist party formally launched an electoral alliance. It teamed up with ten other parties (including the Gen-Z-led National Citizen Party) to contest seats under a single banner.

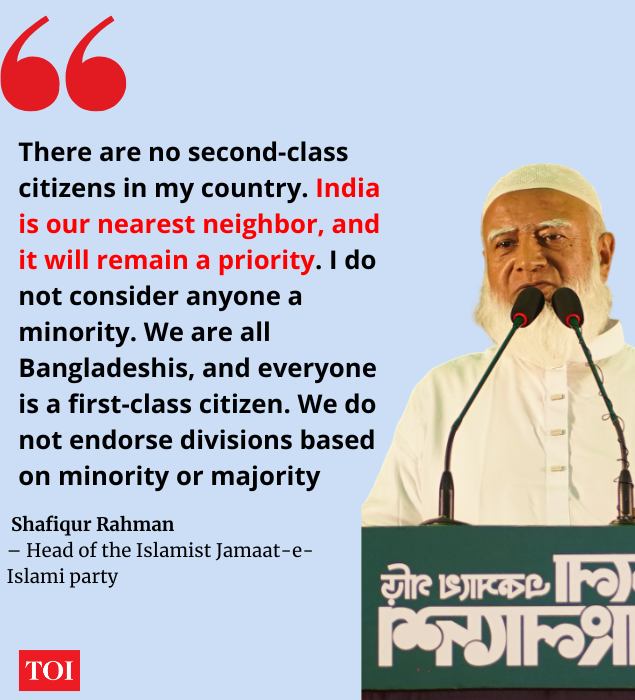

Jamaat’s platform is rooted in Islamic principles, but the party has visibly rebranded itself for 2026. Party leader Dr. Shafiqur Rahman has emphasized social welfare and anti-corruption measures, steering away from its former hard-line image. He told Reuters that Jamaat’s focus is now on “welfare politics, not reactionary politics,” highlighting its medical camps, flood relief and aid for protest victims as examples of a constructive agenda.

Indeed, Jamaat has reached out to demographics it once ignored: Reuters notes that for the first time Jamaat fielded a Hindu candidate for parliament and publicly condemned recent attacks on minorities.On Jamaat-e-Islami’s growing influence, Professor Pant offered a more cautious assessment. “Jamaat’s influence has been growing. The Islamist forces have been growing in Bangladesh,” he said, describing that trend as “a cause for worry”. If Jamaat gains greater sway, “there is certainly a likelihood that Pakistan can re-enter Bangladesh strategically”.However, he emphasised that history places limits on Islamabad’s ambitions. “History is an important marker and it is not that easy for Pakistan to re-establish its credentials in Bangladesh,” he said.Pant also noted that Islamist mobilisation has not gone unchallenged. “We have seen that there remains a strong pushback against the extremist factions in Bangladeshi society,” he said.

NCP: Gen Z party faces defining test

The National Citizen Party (NCP) was born out of the blood and fury of July 2024. The student portest propelled a new generation of activists into formal politics. Formed in early 2025 and led by 27-year-old Nahid Islam, the NCP says it aims to break decades of dominance by the Awami League and the BNP. Its platform centres on tackling corruption, ensuring judicial independence, protecting press freedom and reforming governance through the so-called July Charter. The party has also pledged justice for those killed in the uprising, lowering the voting age to 16, job creation through economic reform and greater women’s representation in parliament.Yet translating street power into votes has proved difficult. Opinion polls ahead of the February 12, election suggest the NCP trails behind the BNP and Jamaat-e-Islami. Lacking funds and grassroots machinery, the party struck an electoral alliance with Jamaat in December, describing it as a “strategic” and not ideological pact designed to prevent instability and electoral sabotage.The move has triggered internal revolt. At least 30 senior figures have opposed the alliance, with several resigning. Critics argue the partnership risks diluting the NCP’s centrist identity and tethering it to Jamaat’s controversial past. The deal has also raised concerns over women’s representation, with only a handful of female candidates fielded under the arrangement.

Why is the region watching closely

What’s the outlook for India?Bangladesh’s ties with India have long oscillated with domestic politics. Under Khaleda Zia’s BNP governments (1991–96 and 2001–06), relations were often tense. Khaleda herself famously positioned the BNP as a “protector of Bangladeshi interests against Indian domination,” raising issues like overland transit rights, the 1972 Friendship Treaty, and disputes over the Farakka Barrage on the Ganges. She refused to grant India unfettered transit of goods through Bangladeshi territory, calling it a threat to Bangladesh’s sovereignty. Khaleda’s alliance with Jamaat exacerbated those frictions. In the early 2000s Jamaat elements in Bangladesh harbored extremists hostile to India. Khaleda’s rival Sheikh Hasina – leader of the secular Awami League – worked closely with India. Hasina’s governments from 2009 onward cracked down on anti-India militants (including Jamaat-linked cells) and resolved various disputes.In the 1970s–80s Jamaat was pro-Pakistan and opposed to Bangladeshi independence.

However, Jamaat’s current leadership is publicly moderating its tone. In private, the party has sought dialogue with India: Reuters reports that Jamaat leader Shafiqur Rahman even met an Indian diplomat (confidentially) earlier in 2025 and said Bangladesh must “become open to each other”. At the same time, Shafiqur has voiced irritation that Hasina “continues to stay in India” after fleeing. This reflects the interim government’s hard line: Bangladeshi leaders have asked India to extradite Hasina for trial, and New Delhi has demurred.In its election manifesto, Jamaat declares it will seek “peaceful and cooperative relations” with all neighbours, including India. Whether this rhetoric will hold in practice is uncertain, but it suggests Jamaat knows India is a critical audience.From India’s standpoint, Pant suggested that “the best case scenario” would be a mainstream party such as the BNP winning the election, “now that Awami League is out of contention”, with Jamaat’s role “contained and limited” rather than decisive. Post-2024 strainsThe revolutionary upheaval that removed Hasina has strained relations with India. Hasina was seen in New Delhi as a reliable ally, and her abrupt ouster took Dhaka into a period of uncertainty. The interim government has been openly critical of India’s hospitality to Hasina. Yunus’s advisers complained that India allowed “incendiary” remarks from Hasina’s exile to go unpunished, and even that Yunus’s first official visit was to China – Bangladesh’s traditional rival of India. In April 2025 Prime Minister Modi met Yunus in Thailand, declaring a desire for “positive and constructive” ties, but also taking the opportunity to raise concerns about alleged “atrocities” against minorities in Bangladesh.Indeed, since late 2024 there have been multiple attacks on Bangladesh’s Hindu minority, often linked to the political turmoil. Hindus (about 8% of the population) historically tended to support the Awami League; after Hasina’s fall, mobs in several districts burned homes and temples belonging to Hindus. Why it matters for IndiaFor New Delhi, Bangladesh is far more than a neighbour; it is a strategic linchpin in south Asia’s evolving geopolitical architecture. The two countries share a 4,000km border, deep economic ties, and common concerns. Historically, India has tried to maintain good relations regardless of which Bangladeshi party was in power. As PM Modi’s handover letter at Khaleda’s funeral made clear, India expects Bangladesh’s “vision and values” – whether from Khaleda or others – to guide partnership building. On Dec 31, 2025, Jaishankar met Tarique Rahman and handed over PM Modi’s condolences, while earlier in April 2025, PM Modi met Yunus, pledging cooperation. Such meetings signal that India will work with the incoming government.A central strategic theme for India has been connectivity with its own north eastern states. The Siliguri Corridor, a narrow stretch of land in West Bengal commonly known as the “Chicken’s Neck,” (something that interim governments leader’s have alluded to much to India’s anger) remains a cause for India’s territorial cohesion because it is the sole land link to the eight north eastern states. New Delhi has invested in alternative logistics and security measures, including a plan for an underground railway line to strengthen this corridor against natural or geopolitical disruption. These infrastructure plans reflect India’s heightened awareness that reducing dependence on this bottleneck is a long-term priority. Access to Bangladeshi ports also intersects with India’s broader Act East Policy, which aims to link India’s north east with Southeast Asian markets. Ongoing infrastructure cooperation, such as expanded rail and road links across the border, has been encouraged in diplomatic dialogues, signalling that New Delhi views Dhaka not just as a neighbour, but as a partner in regional integration. These connectivity and security interests intersect with regional power competition. China has significantly expanded its influence in Bangladesh, particularly since the political transition in 2024, through infrastructure projects, diplomatic engagement and investment. Beijing’s involvement ranges from port facilities to broader development financing. Domestic political shifts in Dhaka have also strained diplomatic engagement. Earlier diplomatic frictions, including reduced issuance of medical visas by India, inadvertently created space that Beijing sought to fill with offers of infrastructure and hospital projects. Water and river diplomacy also remain perennial strategic issues. Shared rivers like the Teesta have long been part of bilateral discussions, with water sharing agreements seen as symbolic of deeper cooperation. Progress on these fronts will continue to be important irrespective of the electoral outcome.

What are the stakes for Pakistan and China?

Beyond ideology and geopolitics, both Pakistan and China are sensitive to economic fallout in Bangladesh. The garment sector, the backbone of Bangladesh’s export economy, remains fragile after tariffs and instability dented orders and investor confidence. A government that cannot reassure buyers, or that imposes policies that unsettle factory owners and foreign investors, will cascade economic pain through the region: lower exports, supply-chain disruption and slower regional growth. That would be bad for China (which trades and invests heavily in the region) and for Pakistan (which looks to Bangladesh as a market and a partner in regional forums). Stability and rules-based governance thus serve both capitals’ material interests. If Jamaat gains groundFor Pakistan, Jamaat’s rise would carry symbolic weight. The party’s historical links to Islamist politics in the subcontinent, and its controversial position during the 1971 Liberation War, have long shaped how it is viewed in Dhaka and Islamabad. A stronger Jamaat presence in government could open warmer political channels between Bangladesh and Pakistan, potentially softening decades of distrust.Islamabad would see opportunities for diplomatic re-engagement, expanded religious and educational exchanges, and closer coordination in multilateral forums such as the OIC. Even incremental thawing would be framed domestically in Pakistan as a geopolitical correction in South Asia.Yet the gains would be more symbolic than structural. Bangladesh’s economy is deeply intertwined with global supply chains and regional powers beyond Pakistan. Any government in Dhaka must prioritise export markets and macroeconomic stability over ideological affinity. Pakistan’s room to convert goodwill into concrete economic advantage would remain limited.For China, Jamaat’s rise presents a more complex equation. Beijing’s interests in Bangladesh are overwhelmingly economic and strategic: infrastructure, energy, digital networks and maritime access linked to the Belt and Road Initiative. China has become one of Bangladesh’s largest trading partners and a key financier of major projects.A Jamaat-influenced administration might not necessarily disrupt these ties. In fact, Islamist parties have often shown pragmatic streaks in foreign policy when economic survival is at stake. If the BNP winsA clear BNP victory alters the dynamic in subtler ways. The party, historically led by the Zia family, has long advocated a nationalist, sovereignty-focused platform. It has at times been critical of what it describes as overdependence on India. That posture could indirectly benefit Pakistan, as a Dhaka less closely aligned with New Delhi might reopen space for Islamabad to rebuild ties.However, BNP leaders have also signalled an interest in diversifying partnerships rather than pivoting wholesale towards any one country. For Pakistan, this means cautious optimism rather than guaranteed alignment. Diplomatic warmth may improve, trade delegations may resume, and symbolic gestures could follow. But deep strategic convergence is far from certain.Economically, Bangladesh’s trade with Pakistan remains modest compared to its commerce with China, India, the EU and the US. But symbolism cannot override economics. Pakistan remains a marginal trade partner compared to China, India and the WestChina’s calculus under a BNP government is more consequential. The BNP has previously engaged closely with Beijing, and China has cultivated ties across Bangladesh’s political spectrum to safeguard its investments. A BNP-led administration would likely continue major infrastructure projects while possibly seeking better financial terms or greater transparency to address domestic criticism.The challenge for Beijing could arise if a BNP government attempts a recalibration of foreign policy to balance China more visibly with Western partners. Efforts to court European or American investment, or to diversify defence procurement, might slightly dilute China’s relative influence. Yet this would represent adjustment rather than rupture.What are the economic implicationsWhichever party prevails, Bangladesh’s economic health will shape the regional equation. The country’s export-driven model, centred on garments, depends on stability, investor trust and access to Western markets. Prolonged unrest or policy uncertainty would dampen growth and affect regional trade flows.For China, Bangladesh is a gateway to the eastern Indian Ocean and a critical node in regional connectivity. For Pakistan, improved ties with Dhaka would signal diplomatic breathing space in South Asia. But neither capital can override Bangladesh’s domestic priorities: jobs, inflation control and social stability.In many ways, this election is less about ideological realignment and more about governance credibility. Pakistan may hope for renewed warmth if Jamaat gains or if the BNP distances itself from India. China will look for guarantees that its billions in infrastructure commitments remain insulated from political swings.

So, what does the future hold?

Bangladesh’s February 12 election is not simply a transfer of power; it is a reckoning with the political order that has defined the country for nearly two decades. The uprising of 2024 shattered the dominance of one party, but it did not resolve the deeper questions about identity, governance and the balance between secular nationalism and political Islam. Those questions now sit at the heart of the ballot.For the BNP, this is a bid for restoration under Tarique Rahman. For Jamaat-e-Islami, it is a quest for renewed legitimacy after years in the wilderness. For voters, it is a choice about stability, ideology and the limits of executive power.Beyond Bangladesh’s borders, the implications are strategic. India will seek continuity and security, China will guard its investments, and Pakistan will watch for diplomatic openings. The outcome will not simply decide a government. It will signal which direction a pivotal South Asian state chooses at a moment of regional uncertainty.But ultimately, this election will reveal something more fundamental: whether Bangladesh emerges from the crisis with a clearer democratic centre, or whether fragmentation and competitive nationalism become its defining features. In a region already unsettled by political churn, the direction Dhaka chooses will resonate far beyond its borders.