Changing The Rules Of Seeing: Sylvia Sleigh’s Male Nudes

The history of Western art is also a history of looking at women. From reclining nudes to Venus gazing at mirrors, the male gaze defined what was aesthetic pleasure for centuries. Female bodies were mere objects for masculine consumption. Anonymous or mythological women would be displayed for the pleasure of male artists, male patrons, male viewers, male male male male.

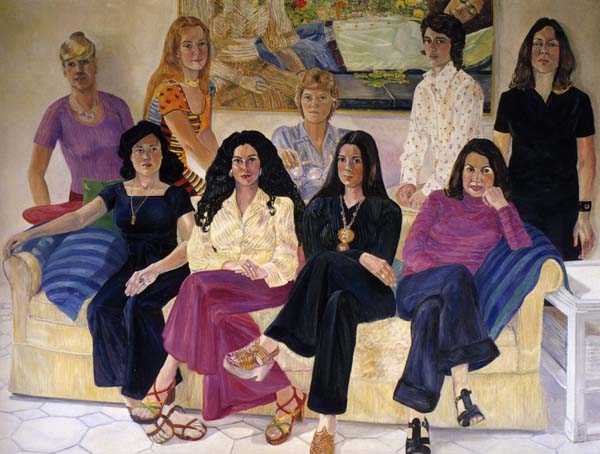

Women would internalise this gaze, surveilling themselves from imagined masculine perspectives. So, how do you tear down a system of looking built over centuries? Sylvia Sleigh’s answer was to reverse that established method. She borrowed art history’s most canonical depictions of female vulnerability and replaced those figures with men she knew.

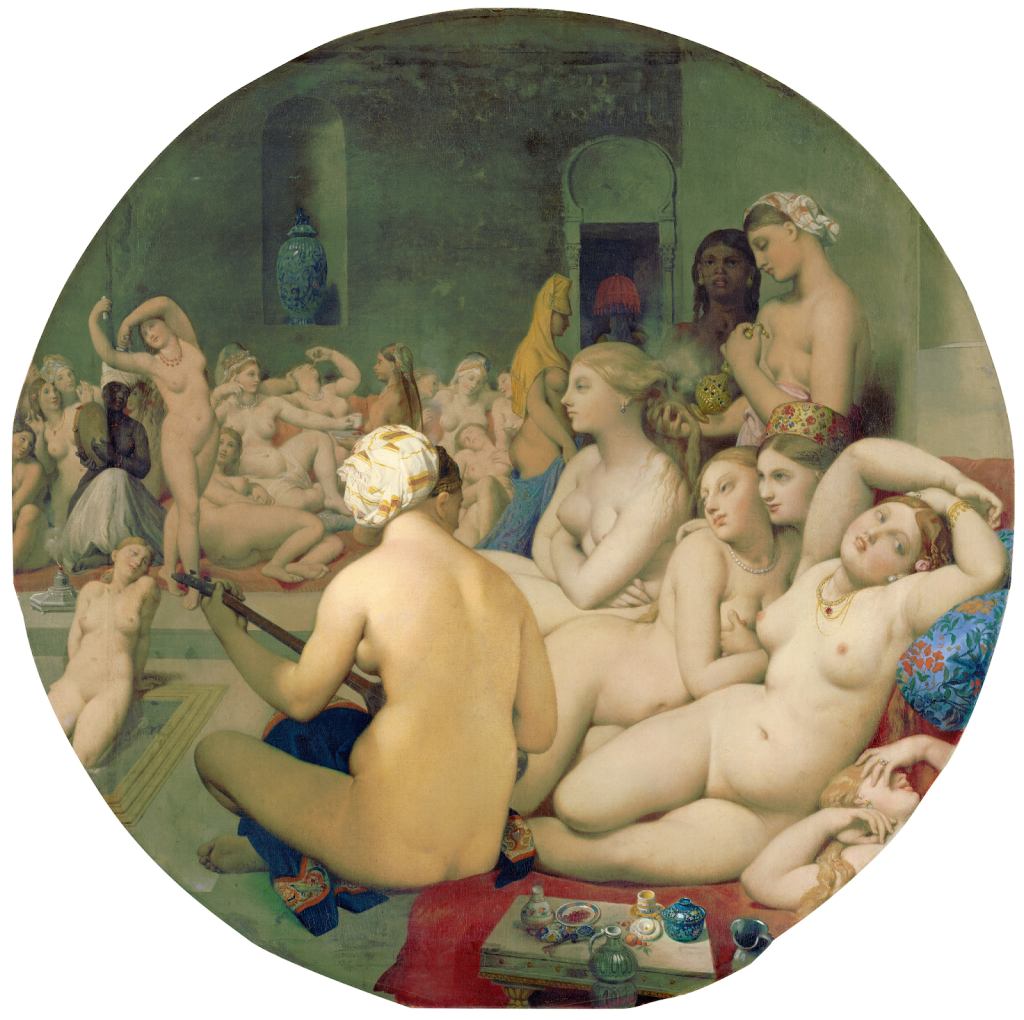

Jean-Auguste-Dominique Ingres’s The Turkish Bath (1862) is the perfect representation of Orientalist fantasy. A harem is filled with languid female bodies offered for male consumption. The women are anonymous, obviously, their particularity dissolved into exotic types. The space is timeless.

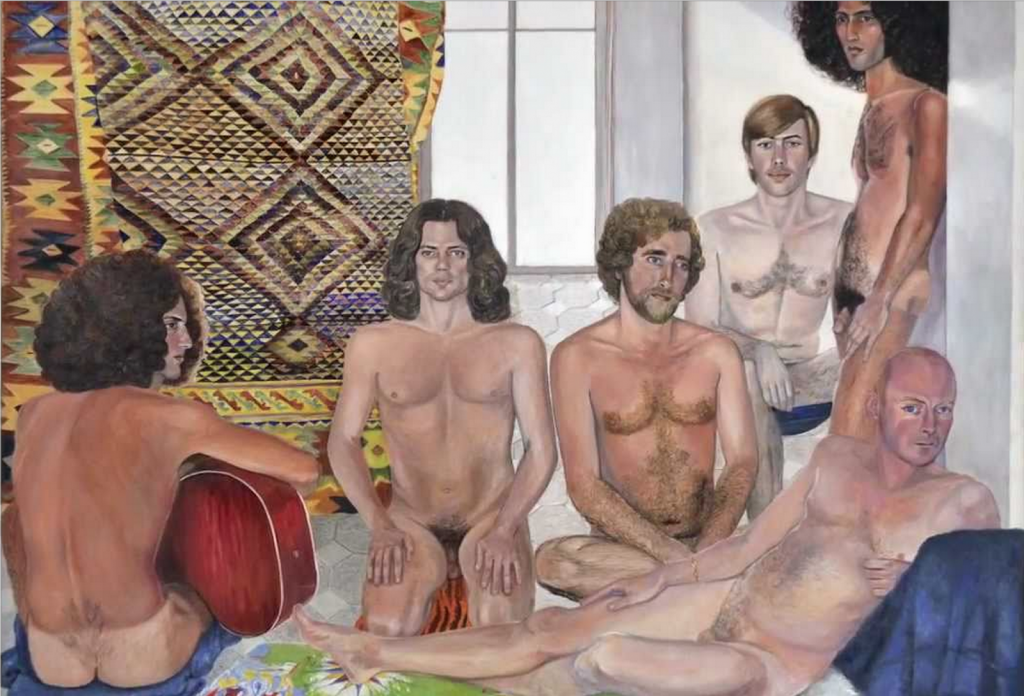

In 1973, Sylvia Sleigh created her own Turkish Bath, but the harem here was her living room. Six life-size male figures sprawled across Turkish carpets in this painting, with her husband Lawrence Alloway prominent in the foreground. You’ll also spot art critics Scott Burton and John Perreault, musician Paul Rosano, other figures from her intellectual circle.

This setting has no fantasy. The clutter of actual domestic space is noticeable, with visible furniture and books. The bodies have no idealisation either; they’re ageing, soft. By transposing men into odalisque poses, she forces viewers to watch something unprecedented: male bodies vulnerable, arranged for viewing in ways Western tradition kept exclusively for women. Seeing male bodies in these positions makes you recognise that the positions themselves were never natural. It’s just that objectification always has been constructed through conventions we’ve learned not to see.

Sleigh painted The Turkish Bath in 1973, the same year Roe v. Wade was decided, the same year the American Psychiatric Association removed homosexuality from its diagnostic manual. Second-wave feminism was reaching institutional victories while simultaneously fragmenting over questions of race, class and sexuality. The New York art world Sleigh was part of was facing its own challenges, with women artists protesting their exclusion from galleries and museums and contesting the male-dominated canon. That Alloway, a curator and critic with institutional power, chose to model nude for his wife’s feminist piece was a public gesture, a visible alignment with feminist critique at a moment when such alignment could damage professional standing.

Moreover, Ingres’s fantasy was colonial, since the The Turkish Bath imagined Eastern women as available for Western masculine consumption. Harems were stock settings for European painters throughout the nineteenth century, spaces where the bodies of brown and black women could be displayed under the guise of ethnographic curiosity. By replacing colonised women with white male intellectuals from New York’s art establishment, she reduces the distance Orientalism required—between here and there, between subject and object, between civilised viewer and exotic viewed. The white male body, historically positioned as universal subject and colonial master, suddenly occupies the position of the colonised feminine other.

Diego Velázquez’s Rokeby Venus (c. 1647-51) is one of Western art’s most celebrated female nudes. Venus reclines with her back to the viewer in this painting, gazing at herself in a mirror held by Cupid. The pose conveys vulnerability, with self-awareness, and passivity, with the faintest gesture toward agency. The painting is iconic for its aristocratic sensuality, its idealised rendering of female flesh.

Sleigh’s Philip Golub Reclining (1971) quotes this pose exactly, but the young man (the son of artists Nancy Spero and Leon Golub) is awkward. His pale body lacks any idealisation. His body hair is visible, his skin texture lacks any polish. Where Velázquez smoothed Venus into aesthetic perfection, Sleigh’s rough realism does away with all that. The rough surfaces prevent fetishisation and resist the smooth consumption that patriarchal representation naturalises.

More importantly, Philip Golub is named and known. He consented to this exposure, understood what Sleigh was painting and why. This matters. The use of identifiable subjects (people Sleigh knew and respected) demonstrates recognition that’s fundamentally different from the anonymous/mythological women populating centuries of male-painted nudes.

Sleigh’s style was often dismissed by critics as technically inferior, lacking the sophistication of her contemporaries. Reviews described her work as “awkward,” “crude,” even “amateurish,” criticisms rarely levelled at male painters whose rough surfaces would be read as expressive boldness or deliberate primitivism. When male painters like Lucian Freud or Francis Bacon rendered flesh specifically, unflatteringly, critics praised their “unflinching honesty” or “raw power,” but when Sleigh painted unglamorous male bodies with visible imperfection, she was accused of technical incompetence.

But it was her roughness that kept the images uncomfortable, that prevented aesthetic pleasure from obscuring the political stakes. That the art world dismissed this as a lack of skill rather than a conscious strategy shows how extremely patriarchal standards of technical mastery remained entrenched in critical judgment, how painting “well” meant painting in ways that reinforced rather than challenged dominant visual hierarchies.

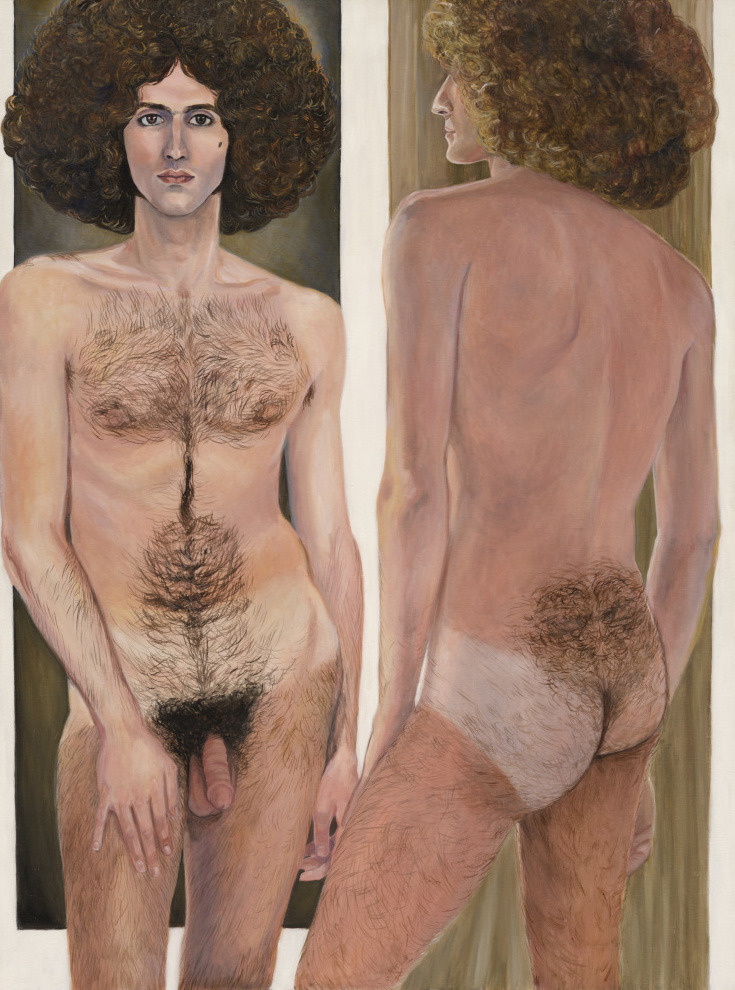

In Double Image: Paul Rosano (1974), the musician appears twice, in frontal and back views, as if caught in a mirror self-confrontation. The particularities of an individual male body, rather than an abstracted masculine form, are visible in soft genitals and body hair. But the doubled perspective also creates a moment of reflexivity, for the subject sees himself being seen and becomes aware of his own status as an image.

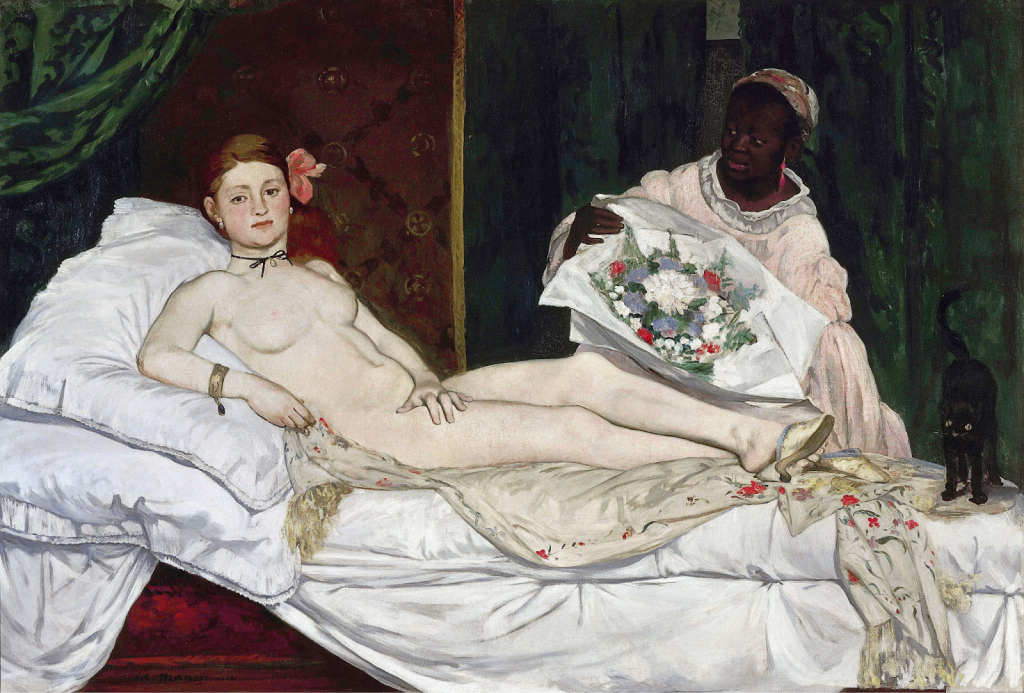

This self-awareness is precisely what classical objectification lacks. When the female nude in Western tradition occasionally gazes back—most famously in Édouard Manet’s Olympia—her gaze (and its return) is read as resistance. A refusal to be purely passive. Classical objectification depended on the viewed figure’s apparent unawareness, their passive availability. Sleigh’s mirrors shatter that passivity. In her mirror confrontation, Paul Rosano, beyond awareness of the viewer, is also confronting his own exposure, watching himself occupy a position long coded feminine.

The mirror, rather than taking on a voyeuristic distance, urges recognition. It insists that looking is always reciprocal, that representation involves two subjects rather than a subject consuming an object.

Does reversal comprise a feminist intervention? Or does it simply reinscribe the binary logic of domination? In 1981, art historians Griselda Pollock and Rozsika Parker challenged Sleigh’s work: “Masculine dominance cannot be displaced merely by reversing traditional motifs.”

Their concern was valid, for because Sleigh’s subjects were identifiable portraits rather than anonymous types, they couldn’t achieve the same depersonalised objectification as the female nudes in, say, Ingres or Velázquez. Recognition prevented true reversal. But while, yes, Sleigh reverses the figures, with men replacing women in odalisque poses, she simultaneously refuses everything else of the classical objectification.

The subjects, instead of being anonymous, are identifiable people she knew and respected. The bodies, instead of being idealised, are rendered with unglamorous particularity that has no fetishisation, but rather bodies that resist fetishisation. The settings, instead of being fantasy spaces, are ordinary domestic interiors. The surfaces, instead of being smooth, are rough, preventing the kind of aesthetic pleasure that would allow untroubled consumption. Objectification requires the erasure of the subject’s humanity, their reduction to type or fantasy, and Sleigh’s works never compromise on particularity or consent. Her paintings highlight that ethical representation requires recognition by seeing the other as a subject with agency rather than an object for consumption.

This is also what feminist theorists mean by the ‘female gaze’, not women objectifying men, but a complete recalibration of the power dynamics that dictate how we see.

The female gaze, in Sleigh’s hands, is inseparable from the ethics of friendship, from networks of reciprocal care that precede and frame the act of representation.

Even the term ‘female gaze’ risks oversimplification. As if there are only two ways of seeing — masculine (objectifying, voyeuristic) and feminine (empathetic, relational). But looking can be of many types and can also work on several levels:

There’s the medical photography’s clinical gaze. It documents without any desire, but also without any care.

There’s the pornographic gaze, which wishes for arousal through depersonalization.

There’s the security camera’s surveillance gaze, which monitors without any familiarity.

There’s the art-historical gaze, which aestheticises and converts bodies into a formal arrangement.

Sleigh’s practice doesn’t just oppose ‘female’ to ‘male’, but offers a communal gaze. A gaze grounded in a prior relationship between artist and subject. She doesn’t photograph strangers or hire anonymous models. She paints people from her life, be they her husband or her friends’ children, people whose subjectivity she already knows, people whose subjectivity she already respects. It’s a gaze informed by actual knowledge of who the subject is beyond their body, what they think, what they’ve consented to, and how they understand their participation.

The female gaze, in Sleigh’s hands, then, is inseparable from the ethics of friendship, from networks of reciprocal care that precede and frame the act of representation.

For centuries, Western visual culture naturalised a division. Men looked, and women were looked at. The tradition of the nude encoded this hierarchy so thoroughly that it became invisible, mistaken for an aesthetic truth rather than a power structure.

Sleigh’s art made that structure visible by placing it where it had never been kept. On male bodies, in domestic spaces. Her paintings expose how objectification operates. By rejecting these mechanisms, Sleigh showed that representation can work in different ways. In her practice, the female gaze didn’t seek power within existing structures. Instead, it tried to change the rules of seeing itself. It established relationships of recognition rather than consumption. It honoured vulnerability rather than exploiting it.

The discomfort her paintings generate is the productive recognition that we’ve been taught to see certain bodies as naturally available for consumption. That this naturalisation was always constructed, always contingent, always open to change.