Violence As Inheritance: Bullying, Masculinity, And Breaking The Cycle In Indian Schools

I don’t remember the first time a hand was laid on me. But I do remember that I simply stopped keeping track after a point. Born into a tight-knit family of first-generation immigrants, I understood early on that our lives were different from those of our neighbours. There were compromises we had to make without question: we had to be on our best behaviour, primed to absorb unprovoked blows, erasing any lingering accent or trace of our mother tongue lest we risk someone’s ire. I often witnessed firsthand what happened when a man from my family got too comfortable in his skin, or when a man from another woke up on the wrong side of the bed.

Even though I was taught never to raise my hand, I became a convenient outlet for extended family to take their frustrations out on—a whipping post personified. The Dairy Milk on offer post-beating became a sweet bribe for my silence. And so I learnt to let them. It was a heavy dose of cognitive dissonance for a pre-adolescent mind: to be loved and bruised in the same gesture, often by the same hands.

Intergenerational violence is well-documented in India. It ties to gender norms where boys learn to conquer and dominate without ever learning to nurture or build community. To break this, masculinity must include both—and be brave enough to explore what exists beyond. Redefining manhood to allow vulnerability helps boys explore and hopefully process anger in healthier ways.

The first act of violence that patriarchy demands of males is not violence toward women. Instead patriarchy demands of all males that they engage in acts of psychic self-mutilation, that they kill off the emotional parts of themselves. If an individual is not successful in emotionally crippling himself, he can count on patriarchal men to enact rituals of power that will assault his self-esteem.

– bell hooks, The Will To Change: Men, Masculinity, and Love, 2004

In an all-boys school in India, violence is largely inescapable. In classrooms where rich and poor sat side by side, violence became the common equalizer: a slap stung the same, regardless of our background. We became hardened to such a degree that the fear of the seven to eight hours spent on campus bought our silence outside it. This “snitches get stitches” culture buried the collective-experience as we upheld a pact no one signed up for.

Our cultural mirror, Bollywood, often complicates the issue. In Munna Bhai MBBS (2003), when weaker students are being ragged, the affable gangster Munna interrupts, demands to be ragged himself, then takes the stage shirtless—flaunting his brawn to intimidate the seniors. What starts as a humorous stand-off ends with the bullies humiliated, forced to strip on stage in a reversal framed as “justice.” While laughter is a great instrument to explore and process trauma, it felt like a lost opportunity; it may subtly suggest that the way to stop bullying is to become an even bigger bully—which in my experience is often one of the first male attempts to break the cycle.

3 Idiots (2009) plays a “pants-down” prank for laughs, despite its critique of the education system. These depictions often normalize ragging as “fun,” or suggest “become the bigger bully,” inadvertently downplaying the trauma that led to landmark legislation like the 2009 Aman Kachroo case.

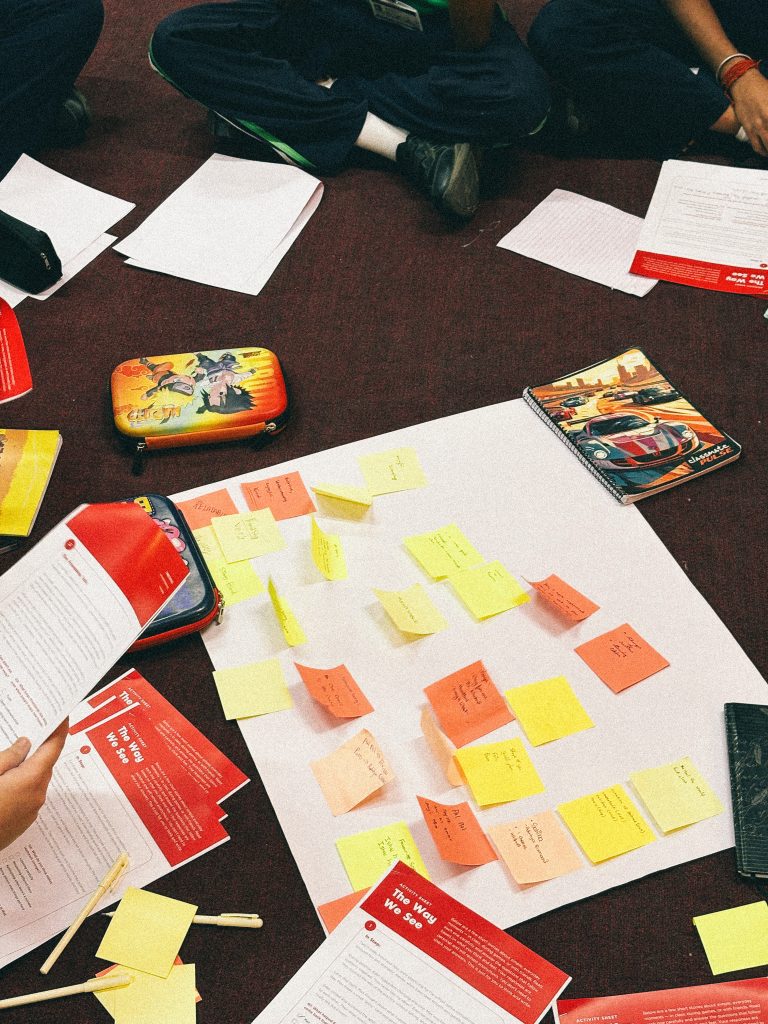

These patterns of repression and anger don’t just live in memory. They show up in the boys I meet today. Through Facilitation Circles run by Veera Foundation, I’ve worked with students from all kinds of backgrounds and keep noticing the same patterns: anger, repression, and rising aggression.

One Circle stands out. I was with an eloquent and precocious 11-year-old, ‘X’. He possessed a kindness and respect that belied his age, yet most jokes made by his peers were at his expense. When our session began, he refused to sit on the ground, claiming an injury.

I suspected the three “troublemakers” in the group were involved. I split them up—making A an ally, sending C to a different group, and B an ordinary participant. When A started doing push-ups unprovoked next to another Circle, I didn’t punish or reprimand him. Instead, I asked him to do it in our designated area, and then joined him—20 reps, 3 sets. If we were going to do something, we would do it well. By the second set, the kids were tired but attentive enough to rejoin the Circle.

They eventually warmed up, feeling safe enough to confide in me. B, allegedly a bully himself, asked me: “How do I trust someone?” and “How do I know if someone’s fake?” These are questions we all contend with, yet they felt like a soft slap in the face, reminding me of the complex emotions of adolescence and the disaster that occurs when that connection, that safety is lost.

In that moment he was a simple, vulnerable child sincerely asking for help amidst what could possibly be all the confusion that one contends with around adolescence. I remember it vividly.

I was once that “space-cadet,” happiest when chasing butterflies, until kids found ingenious ways to arrest my attention. After years of returning home battered, and after puberty hit, a female-relative finally told me: “This is the last time you’re coming home beaten up. Don’t show up like this again.” Nonetheless, I “toughened up.”

For a while, I let my fists and limbs reply to the slightest provocation. Initially for self-preservation, the power eventually became intoxicating. I dragged other kids into the cycle I had longed to escape. My aggression manifested as constant bust-ups with peers and authority figures. Thankfully, I eventually found an outlet in sports and music, long enough to keep me out of trouble.

The statistics reflect this lived reality. A 2024-2025 study by Bullying Without Borders reported 160,000 serious cases in India; other surveys suggest up to 60% of students are affected. In boys’ schools, this is dismissed as “toughening up,” tied to a toxic masculinity that prizes conquest over empathy. This normalization contributes to a rising tide of student suicides. In November 2025, the death of 16-year-old Shourya Patil in Delhi sparked national protests. From Jaipur to Madhya Pradesh, stories emerge of children jumping from buildings after ignored pleas. NCRB data reveals that India accounts for one in nine global student suicides, with bullying and institutional neglect as key factors.

Growing up as a man, violence always felt like something I inherited—harsh beatings from home, passed down through family, in a society that never showed us how to handle our anger. We weren’t encouraged to see anger as energy that could be used constructively; instead, it simmered, erupting as mockery of the weak or punishment of anyone who dared to be different. Within this rigid mould of masculinity, vulnerability was weakness, and dominance was the only proof of manhood.

While India’s National Education Policy (2020) emphasizes holistic development, transformative approaches still lag. We must embed gender sensitivity as early as ages 3 to 6, challenging stereotypes in play and stories. We must also teach constructive outlets—treating anger as energy that can be redirected through movement, creative expression, or naming emotions.

Teacher sensitization is the final, vital piece of the puzzle. Educators must be trained to recognize withdrawal and mood changes, moving away from the “boys will be boys” shrug. Schools need robust policies: anti-bullying committees, mandatory counselors, and safe, anonymous reporting.

Therapy, connection, and safety break cycles. Feeling violence as inheritance needn’t be fate.

Looking back at that boy I was—quietly absorbing blows, picking apart pieces of myself to survive—I know now that the real task wasn’t to toughen up. It was to speak up, to feel the anger without letting it own me, and to choose something different.

But who could I have spoken to when no one around me seemed equipped to handle those complexities? What happens to boys who need help but find no real avenues for it? Where do these boys go? That’s the question that stays with me. I hope we can give today’s boys the choices we didn’t have—the spaces, the listeners, and the tools—so the cycle has some chance of ending with us.

*names changed for privacy

Gavin George shapes Communications and Culture for the Veera Foundation (@veeravoices), crafting stories and campaigns that invite boys and men to explore vulnerability and empathy—without judgment or lectures. With nearly a decade in media and storytelling, plus a psychology grounding from Ambedkar University, he turns complex ideas into human, relatable narratives.

A multi-creative soul, Gavin moves between words, music, and visual arts. He believes creativity, in all its messy, joyful forms, is one of the most powerful ways to heal, build bridges, and reimagine what it means to be a man.

His writing examines how rigid norms shape lives from childhood to work, and how curiosity and connection can rewrite them. He lives in Delhi, believes chai fixes most things, and is always up for a good story (or a terrible joke).