Blinis and bullies: Memories of a non-aligned childhood

In ‘The 18th Brumaire of Louis Napoleon’, Marx writes: “Hegel remarks somewhere that all great world-historic facts and personages appear, so to speak, twice. He forgot to add: the first time as tragedy, the second time as farce.”

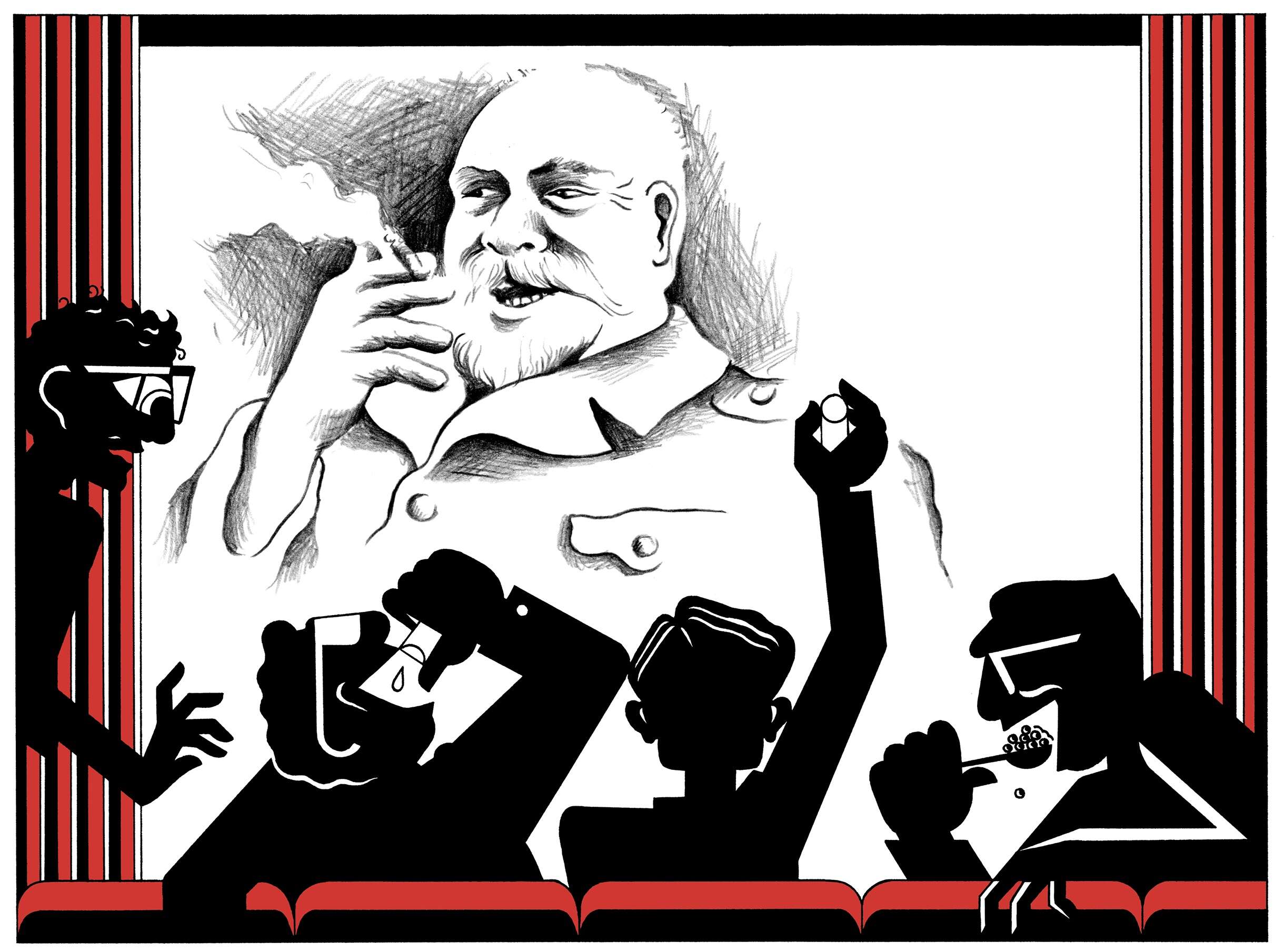

I grew up with some simple truths. One of them was that we are non-aligned. But also, that the USSR was our friend and the US our enemy, which might make you think otherwise. A friend explained: ‘We are the kind of kid who wants to be friends with everyone, but there are always some bullies who want to tell you who else you can hang out with.’ I must say that I was not entirely persuaded; we all adored Mrs Gandhi for saving the poor brave Bangladeshis, but she seemed no push-over. Her jawline came across very clearly in the photos: I found it hard to imagine anyone trying to bully her.I spent hours staring at photos of Nixon and Brezhnev, trying to figure out who I trusted less. It was a close call. Both had bushy eyebrows, but Brezhnev’s looked like giant caterpillars. Nixon often wore a smile, but that made his innate untrustworthiness so apparent that I slightly preferred the dour face that Brezhnev offered. As I said, it was a hard call.

As I grew and passed into teenage, it became evident that there was more to it than personalities. Ultimately, a lot of it was about two different ways of running the economy — whether capital is primarily owned by individuals or by the state. Each had its own rationale and its devotees. In India, we were trying to thread a path between the two — we had our Tatas and Birlas, but most steel plants, for example, were owned by the government — which made us a target for propaganda from both sides. As a non-aligned family in a non-aligned nation, we received both shiny Span, with its gallery of intense American faces, and the more grainy Soviet Desh, featuring buxom blondes next to piles of golden wheat, each touting the success of their respective systems. I must confess that in terms of converting me to their way of thinking, both could have done with some more oomph.

The real privilege, however, was the film screenings. My parents, as one-time US residents, would regularly get cards to the showings at the United States Information Service. The invites to Gorky Sadan, which was the Soviet equivalent, came via our parents’ Soviet-connected friends, and tended to be more sporadic.

By this time, the Emergency had come and gone, and Mrs Gandhi fell from her pedestal, but in my more mature judgement, the Soviets had to be the good guys. After all, I was for equality and the Soviet Union was socialist. So, I was slightly sad to discover that the Americans had much better films. The Russians had great classics — Eisenstein, Pudovkin and their like — but the more contemporary cinema tended to be quite bland. The good guys won and the bad guys lost, and nothing much happened in between. By contrast, the Americans offered the gritty Sam Peckinpah and the intense John Huston, but also the rambunctious humour of Howard Hawks and the sweetness of Billy Wyler.

When I said that to a left-leaning friend, he responded that when the Russians get to know you, they invite you to nice parties where Russian vodka and caviar is served. I thought that was an odd answer— how does that justify the mediocre filmmaking? — but the thought of cocktail parties at the Russian consulate stayed with me. I would try to imagine what Russian canapés would be like, but with no internet to help me, I didn’t get very far. Now I know of buckwheat blinis served with sour cream topped with smoked salmon or trout and maybe a few capers, or if you wanted the blinis sweet, with varenye, the wonderful Russian preserve that has whole berries floating in it. There might have also been potato and cheese pierogis, Russia’s answer to batata vada, dilled cucumbers and pickled mushrooms, little Russian sausages redolent of garlic and shah jeera, and even perhaps some caviar on little toasts. But my attachment to Russia has long faded.

My story of disillusionment with the USSR isn’t so different from what so many others have written about so beautifully, but it started, I think, with the invasion of Afghanistan in 1979, which seemed to be a naked exercise of pure power. It was also, according to my old friend and former foreign secretary, Jagat Mehta’s ‘The March of Folly in Afghanistan’, a huge strategic blunder: for the Russians, who got embroiled in an unwinnable war; the Americans, who ended up financing the rise of the Taliban; and the Indians, who toed the Soviet line and betrayed our old friends, the Afghans.

I was reminded of all that because of a turn of events that no one could have anticipated a year ago. Russia is now again our best buddy, Ukraine is today’s Afghanistan, and America seems to be back in love with Pakistan, just like in the 1970s. The one difference is that the Trump-Putin bromance seems to have resumed, so we seem to be the only ones left out of this happy party.

Of course, it is not the same Russia. The Soviet state collapsed soon after the Afghan invasion. That disastrous war might have had something to do with the timing, but we now know that the Soviet economy was in crisis starting in the early 1970s and by the 1980s, growth had all but stopped. The world did not necessarily see this, thanks to the creative accounting by the Soviet national income statisticians, but people on the ground knew, and when Gorbachev came to power in the mid-1980s, he realised there was no choice but to radically reform the system.

Gorbachev’s Perestroika or restructuring was based on the insight that control over the economy was vastly over-centralised. Too many decisions about which firm in distant Siberia would buy what inputs from where (perhaps a firm in equally faraway Azerbaijan) were made by some apparatchik in Moscow, who knew very little about either side. Moreover, neither side was supposed to change partners, so any fluctuation in the supply or demand for inputs was a big threat to the other side. Cultivating trading partners, vodka and caviar at public expense for friends and family was very much the norm. In addition, prices were fixed, so when the demand went up (say because there was demand for them in Iran or China), there was a strong urge to sell on the black-market and claim that the dog ate the inputs. At some point for example, an Azeri firm, claiming ethnic conflicts in the area, diverted the compressors it was meant to deliver to its counterpart in Siberia, with the result that a large number of oil wells froze and oil production took a hit.

To fix this, Gorbachev offered firms autonomy to source their inputs, but, alas, not the right to set their own prices. This made the diversion problem worse, since those who had a secret stash of cash or caviar could claim all the inputs. This precipitated a number of crises, culminating in the unravelling of the Soviet model. By 1992, the Soviet Union was gone, and Russia was in a capitalist free-for-all.

The Russians and their Western advisors (mis?)read (deliberately or otherwise) the experience of Perestroika as saying that there is no option but to go for full private property immediately. Ownership rights on firms were handed out to everyone. Since the state had just given away its assets and could no longer afford subsidies, price controls had to be lifted all around. Chaos ensued, with some firms that were kept in business by the price controls going out of business. Many people lost their jobs, but since the new ownership structures were still in situ, new jobs were yet to take their place.

The prices of essential goods, long controlled, skyrocketed. As poverty and despair exploded, the average person had no choice but to sell those ownership rights for bread and shelter to a small cabal of black-marketeers and past members of the caviar and vodka set, who had managed to squirrel away some wealth in the egalitarian Soviet past. This is how we got the famous Russian oligarchs.

It seems that the rise of Putin was a direct result of the combined effects of the chaos that made people value stability over all, and the preference of the oligarchy for someone of their own kind. It is sometimes alleged that the Russian President may be the richest man on earth.

We will never know what other path Russia could have taken. It is true that there is a general tendency towards oligarchies in market economies driven by the dominance of brand names and the value of controlling social networks, and being nimble in dealing with regulations. According to French economist Gabriel Zucman’s research, the share of total national wealth of the top 0.00001% (just 19 households today) in the US went from 0.2% in 1980 to 1.8% in 2024. Something similar is happening in India: according to the Economist, India’s share of billionaire wealth, derived from what the magazine calls crony sectors (sectors where regulation and government support plays an important role), rose from 29% to 43% between 2016 and 2021. Maybe a part of it is, sadly, in the DNA of our times. Nonetheless, it is instructive that China was very careful to avoid the Soviet path — price controls were lifted gradually and while private capital was tolerated and even encouraged, the state continues to control a large part of the national wealth.

One often doesn’t know what Trump really believes and what he just says because he feels like being nasty, but is oligarchy the reason he equated us with Russia as “two dead economies”? If so, he should worry about the US as well, but perhaps we should also worry about the company we keep?

That said, food does not have to be political. I still remain a fan of the Russian chilled soup Okroshka, which could have also been served at those Russian parties (I am imagining all this — maybe they just served samosas or nothing).

This is part of a monthly column by Nobel-winning economist Abhijit Banerjee illustrated by Cheyenne Olivier

Facebook

Twitter

Linkedin

Email

Disclaimer Views expressed above are the author’s own.

END OF ARTICLE