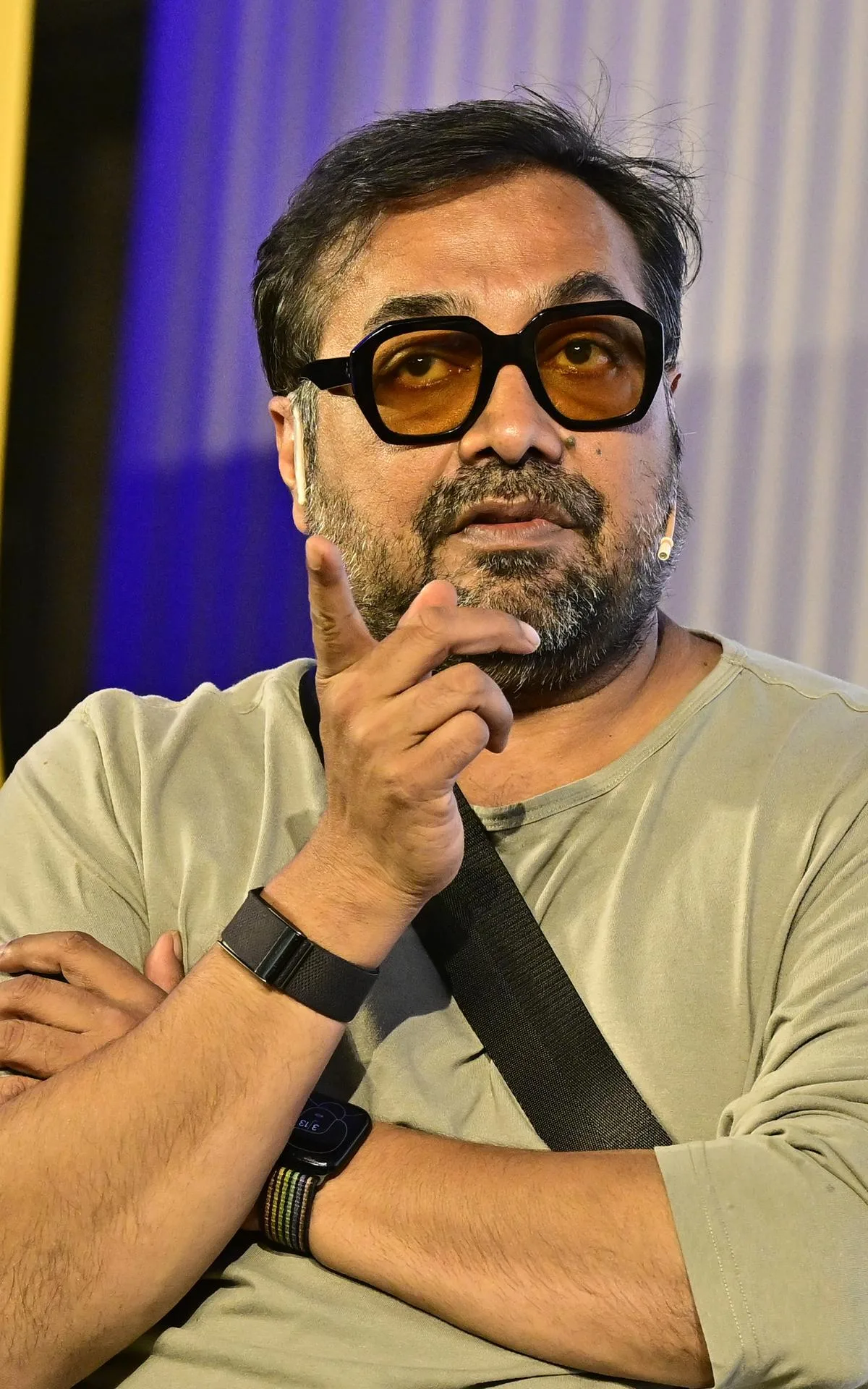

Anurag Kashyap Says Making ‘Gangs of Wasseypur’ Or ‘Black Friday’ Would Be Impossible In India Today – Woman’s era Magazine

Filmmaker Anurag Kashyap has offered a candid assessment of the state of Indian cinema, saying that bold films like Gangs of Wasseypur and Black Friday could not be made in India today. In a recent interaction, Kashyap reflected on the creative freedom that existed when he made those critically acclaimed films and contrasted it with what he sees as a more restrictive environment for filmmakers now, especially when stories delve into politics or real-world events.

Kashyap’s comments come against the backdrop of ongoing debates about censorship, creative expression and the challenges of tackling sensitive topics in films. Both Gangs of Wasseypur and Black Friday are considered landmark films in contemporary Indian cinema. The former is a sprawling crime saga spanning decades, while the latter is a gritty dramatization of the 1993 Mumbai blasts and the events surrounding them. Both films drew attention for their unflinching storytelling and distinctive style, earning praise at home and abroad.

During his remarks, Kashyap suggested that the environment which allowed him to make those films is no longer present in the current cinematic climate. He said that political pressures, risk-averse producers and an increasingly cautious approach to content mean that films addressing controversial subjects or real historical events are harder to realise.

“What was possible then, seems difficult now,” Kashyap said. He reflected on the freedom filmmakers had a decade or so ago to explore storylines without constant fear of backlash or regulatory hurdles. According to him, the creative latitude that enabled him to make Black Friday, a film based on investigative writings about a real terrorist attack and Gangs of Wasseypur a narrative inspired by criminal histories, would be much more difficult to navigate today due to socio-political sensitivities and industry caution.

Kashyap’s comments also touched on the broader climate around political cinema. He argued that films which engage with contemporary issues, real personalities or politically sensitive events face greater reluctance from financiers and distributors, who fear controversy could affect box office or invite social media outrage. This, he believes, leads to a narrowing of what is considered “safe” subject matter in mainstream film projects.

The filmmaker referenced historical precedents of cinema engaging with politics, including works that examine authoritarian regimes or highlight controversial historical moments. He compared the present environment with times when filmmakers internationally have taken on powerful figures or sensitive topics, noting that such projects can provoke powerful cultural conversations. In suggesting that certain films might be more difficult to make now, Kashyap pointed to an atmosphere in which artistic risk is tempered by commercial caution.

Reaction from peers in the industry has been varied. Some filmmakers and writers have echoed Kashyap’s views, acknowledging that the landscape for ambitious, politically charged films has changed over time. They noted that audiences today, as well as producers and platforms, often prioritise entertainment that conforms to established formulas over narratives that challenge prevailing narratives or examine complicated histories.

Others, however, have pushed back at the notion that such films are impossible to make. They argue that independent cinema and digital platforms continue to offer space for diverse voices and that filmmakers can still find ways to tell bold stories, even if the path is more complex than before.

Kashyap’s reflections have stimulated renewed discussion about creative freedom in Indian cinema and the role of filmmakers in pushing boundaries. His own filmography, which includes not only Gangs of Wasseypur and Black Friday but also other commercially and critically bold projects, is frequently cited as evidence of cinema’s capacity to engage deeply with narrative and social commentary.