What Charlotte Brontë’s ‘Villette’ Can Teach Us About Women, Independence, And Refusing To Settle

Women have always been at the centre of an ever-present dilemma, navigating a choice between settling down in a romantic relationship or striving for professional successes. But, what if the most radical thing a woman could do wasn’t finding love, but refusing to make it the center of her story? In 1853, Charlotte Brontë wrote Villette, novel so unapologetic in its honesty about the female experience that even today, it continues to surprise its readers with brilliant exploration of its female protagonist and her life choices.

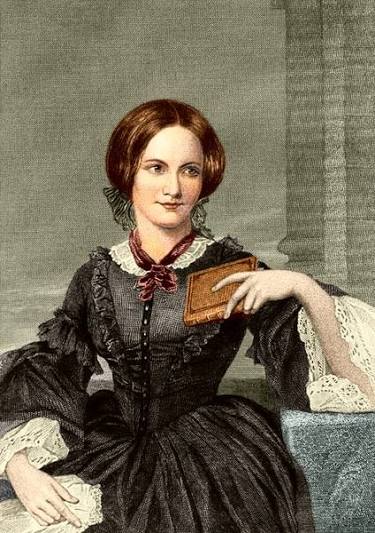

Writing in the Victorian Era (1837-1901) which was marked by a deliberate exclusion of women from the public sphere, the Brontë sisters attempted to represent their female protagonists with a sensitive psychological depth, breaking conventions set by the male literary hegemony. Charlotte Brontë, particularly known for Jane Eyre, contributed to the pioneering of female-centric stories that essentially subverted the expectations of its Victorian readers, paving the way for narratives that moved away from the idea of a woman being represented in relation to a man.

Although there is a presence of male love interests in her stories, they are relegated to a passive space with the woman’s psychology taking on a more important position. This idea of a melancholic female protagonist is beautifully captured in her lesser-known work, Villette. The story follows the journey of Lucy Snowe, who despite her quiet disposition, strives for an independent life. Through the first-person narrative, readers get a glimpse into the complex mindscape of Lucy’s thoughts and desires that often come in direct conflict with her external world. Although Lucy is presented as a timid personality, her characterisation isn’t one-sided. Her dynamic nature only evolves as she navigates her social position as an outsider in an unknown country and the fictional town of Villette.

Moral codes of the Victorian era in Villette

This is where the historical and cultural context of the Victorian Era comes into effect. This period’s upper classes were governed by firm moral codes of conduct, placing women at the receiving end of it. In Desire and Domestic Fiction, Nancy Armstrong argues how the domestic novels of this era actively created gender ideologies. She highlights how novels taught middle-class women to exercise power through moral and domestic values rather than economic or political means. These classes prided themselves on the notion that their women didn’t have to ‘work’ and thus could engage in leisure activities such as embroidering, painting, dance, and music.

This idea is captured by the two minor female characters in Villette, Ginevra Fanshawe and Miss Paulina, who had access to a refined education and high society parties. Interestingly, this sheltered upbringing also led to their infantilisation, wherein the former readily accepted the theatrics of it and the latter tried to show her resistance but eventually gave in. They inhabit a more traditional approach with their ultimate aim residing in a successful marriage alliance.

There are multiple instances in Villette where the narrative reminds its readers regarding Lucy’s approaching spinsterhood, a term most famously associated with the novels of Jane Austen and attributed to women in her early and late twenties, who “failed” to secure a respectable partnership for themselves.

There are multiple instances in Villette where the narrative reminds its readers regarding Lucy’s approaching spinsterhood, a term most famously associated with the novels of Jane Austen and attributed to women in her early and late twenties, who “failed” to secure a respectable partnership for themselves. This was often linked to the necessity of financial security which, in most cases, could only be secured through a marriage.

The solitary traveller

Lucy Snowe, however, exists outside this delicate doll house and manages to enter the working-class space, allowing her to secure a respectable means of livelihood for herself. In the beginning of her journey, she travels alone to an alien space without male protection. Those parts carry a sense of dread with descriptions of Lucy walking empty lanes during night to eventually reach her future place of employment. This journey becomes a necessary step in her life for an ultimate realisation of her true potential.

The small world of Villette becomes a space where tradition and modernity, in the form of its female characters, co-exist together. The boarding school, referred to as Rue Fossette, becomes a place of refuge for Lucy, where her employment as an English teacher provides her with a sense of purpose, and a new found faith in herself.

In fact, Charlotte Brontë herself worked as a governess but was quick to criticise the restrictions it placed on female teachers who weren’t treated with respect from their wealthy employers. She sprinkles these autobiographical elements to offer Lucy the freedom to choose her life path that most women were denied. She establishes a female head of the institution in the authoritative figure of Madame Beck whose strong sense of surveillance adds tension to the story. Despite her interventions, Lucy respects her calmness while undertaking the most difficult tasks as a manager of an entire estate.

Their existence is defined in terms of a solitary but an independent life where they successfully challenge and subvert the systems of patriarchy that work on their subordination.

Despite having children, Madame Beck doesn’t fit in the conventional setup either, since she also acts without the supervision of a male figure, often existing in the form of a husband. Their existence is defined in terms of a solitary but an independent life where they successfully challenge and subvert the systems of patriarchy that work on their subordination.

The emotional cost of independence

The most significant section of Villette is perhaps Chapter Fifteen, ‘The Long Vacation,” that captures a haunting account of Lucy’s emotional breakdown, as she is forced to confront her loneliness during the holiday break at Rue Fossette. There is a sensitivity with which Brontë describes her miserable longings as she perceives a future devoid of hope. She writes,

‘Even to look forward was not to hope: the dumb future spoke no comfort, offered no promise, gave no inducement to bear present evil in reliance on future good. A sorrowful indifference to existence often pressed on me, a despairing resignation.‘

This existential dread manifests itself in endless walking on the streets as an act of expressing her anguish, culminating in her unfortunate fainting. Here, a stream of consciousness technique is employed to create a sense of emotional restraint owing to Lucy’s detached sense of self. Her characterisation becomes an enigma of sorts. It is in her reunion with Graham, her childhood friend, where she gradually learns to express her vulnerabilities. Despite developing an unrequited love towards Graham, their companionship remains platonic, a concept quite novel in works where women and men were shown either as partners or family members.

There are several moments in Villette when Lucy confidently asserts her identity- whether it be denying to accompany Miss Paulina as a paid companion or refusing to convert to Catholicism. Her acts of defiance work to add layers to her complex subjectivity as she relentlessly pursues freedom. Towards the end, when her romantic affections are realised in the form of another teacher, M. Paul, she continues to work on her career as a teacher, therefore denying any form of resignation.

Despite the ambiguous ending hinting at M. Paul’s possible death, the narrative doesn’t lose its novelty in asserting Lucy’s independence, since it is about her journey of self-discovery.

M. Paul respects her intellect and desires, and together they enter into a partnership based on mutual respect and shared professional interests. Despite the ambiguous ending hinting at M. Paul’s possible death, the narrative doesn’t lose its novelty in asserting Lucy’s independence, since it is about her journey of self-discovery. The readers are asked to imagine these characters living a happy and a prosperous life, one where they refuse to settle and give in to the circumstances.

Lucy becomes an independent headmistress of her own school, similar to Madame Beck, further emphasising the unconventionality of such a story. In an era that continues to be dictated by the interests of patriarchal value systems, forcing women to navigate impossible expectations, Lucy Snowe’s rejection of romantic fulfilment and an acceptance of a life built on her own terms reminds the readers of the value in living a truly unapologetic life despite its uncertainties and fears. Nearly two centuries later, her quiet rebellion in Villette feels more urgent than ever.