From Allegation To Alibi: The Architecture Of Belief And Disbelief In The Shamik Adhikary Case

Trigger warning: violence and sexual assault

A man builds a public image as an anti-establishment voice. So when allegations of sexual violence surface, the defence doesn’t engage with the allegations — it reframes the man himself as the real victim. Sounds familiar? This pattern is not new. Male political victimhood has become a powerful cultural currency now-a-days.

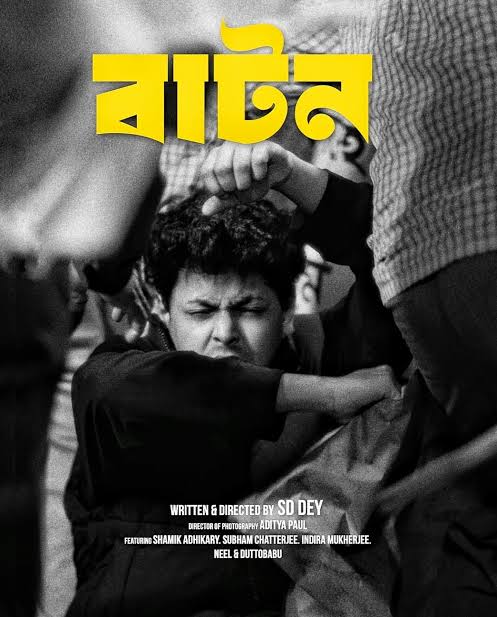

Kolkata recently witnessed a similar situation. Shamik Adhikary, known online as ‘Nonsane,’ was arrested by Kolkata Police following a complaint by a 22-year-old woman. She alleges that she was kept inside his home for hours, assaulted, threatened, and sexually violated. A local court sent him to police custody, and the case is now under investigation.

The cultural currency of male political victimhood

Yet, instead of focusing on the allegations, the spotlight quickly moved elsewhere. His parents, his followers, and the leaders of the BJP claimed that he was being falsely framed by the TMC because of an anti-government reel he had made.

But both the deeds can be true at the same time. A man can oppose authoritarian politics publicly and abuse a woman in private. One does not cancel out the other.

The problem begins when public speech is treated as proof of personal morality. In such a case misogyny slips through. Violence is dismissed as “irrelevant drama,” and the woman becomes an inconvenience—someone distracting people from a larger political “cause.” She becomes collateral damage.

Male political victimhood works because it borrows the language of justice, while quietly shutting the door on justice for women.

Molesters became “marchers”

Shamik’s video may have gone viral. It may have received likes and shares. But neither he nor his reel had been the driving force of the R.G Kar protests or any other movement. He was not such a threat that the state would need to “plant” a woman a year and a half after the R.G. Kar incident to silence him.

But neither he nor his reel had been the driving force of the R.G Kar protests or any other movement. He was not such a threat that the state would need to “plant” a woman a year and a half after the R.G. Kar incident to silence him.

However, since August 14, 2024, we have repeatedly seen that many self-declared “marchers” and activists are themselves accused of molestation. Naming them is not sabotage—it is accountability. As it turns out, Shamik appears to be one of them.

That is why this conversation cannot stop at one incidence of rape. The rape culture—a culture where poor upbringing, entitlement, and unchecked male authority make it frighteningly easy for men to cross boundaries, should be in conversation.

Partisan narrative vs actual narrative

Political backing, whether from BJP or CPM for the perpetrator or from TMC for the survivor only adds to the complexity. None of these parties act out of concern for justice; they act for votes. In the meantime, the focus of civil society must remain on the survivor and on the crime.

Does the narrative of the survivor consist of contradiction? It does not seem so. It may sound dramatic, but it is entirely possible. In fact, her version aligns closely with what Shamik’s parents have admitted, though they were actually trying to defend their son.

Typical parental enabling of male violence

Shamik’s parents admitted that he hit her—claiming it was ‘just one slap.‘ Her injuries suggest otherwise.

They admitted they did not let her leave at the wee hours of night for her own safety. If their son had already injured her at home, how was the home safer than outside? If they were truly concerned, why didn’t they drop her home themselves?

They admitted they did not let her leave at the wee hours of night for her own safety. If their son had already injured her at home, how was the home safer than outside?

They said he got angry and snatched her phone because she was talking to another influencer, normalising jealousy, crossing boundaries and violence.

At one moment, the father hints that the girl may have had many relationships suggesting typical slut-shaming. The next moment, both parents call her a ‘good girl‘ who is being influenced. What does “good girl” mean to them? One who stays silent after being hit?

They admitted that Shamik bought concealer to hide her bruises. That alone proves the injuries were real. Whether she asked for it is irrelevant. The moot point is, she needed to conceal bruises because she had them.

Shamik represents a system of entitled upbringing that excuses aggression. Suicide threats and emotional manipulation are also common tactics used by abusers. They are not taught that even if she is a girlfriend and even if she “cheated” (the girl denies both claims), that can not be an excuse of violence.

Shamik represents a system of entitled upbringing that excuses aggression. Suicide threats and emotional manipulation are also common tactics used by abusers.

When parents insist that violence be ‘handled internally,’ or defend their son’s anger, or reduce abuse to ‘relationship trouble,’ they turn the home into a space of impunity. This is structural enabling, not emotional blindness.

Secondary victimhood and the digital world

Today, belief itself has turned into a public performance. On social media, believing or suspecting a survivor is no longer just a moral choice—it is something people display through reactions, emojis, reposts, and sometimes through silence. Survivors are expected to behave in specific ways. They are expected to look ashamed, broken, helpless and too deeply affected to go to the police. If they speak clearly, they are doubted. If they speak with anger, they are attacked. If they take time to process what happened, they are accused of lying. If they file a complaint quickly, they are called manipulative.

Victim-blaming has always existed. What is new is the scale and intensity of exposure. Every word, every pause, every expression, every decision is dissected by strangers. Disbelief becomes collective. People bond with each other through doubt and hatred. Skepticism is no longer about seeking truth—it turns into a kind of sadistic pleasure.

There is a thrill in tearing a woman down. There is pleasure in proving her “wrong.” There is satisfaction in exposing her as “not perfect enough” to be a real victim. This is how violence continues long after the actual assault ends.

Despite all of this, this woman walked away after the very first incident of intimate violence. That takes courage. More importantly, she filed a complaint.

This matters more than people realise. She did what society constantly demands women to do—”go to the police,” “use legal channels,” “adopt due process.” And when she did that, she was still attacked, doubted, and humiliated.

She did what society constantly demands women to do—”go to the police,” “use legal channels,” “adopt due process.” And when she did that, she was still attacked, doubted, and humiliated.

This tells us something deeply uncomfortable about the world we live in. It tells us that the problem is not how women respond to violence. The problem is that society does not want to believe them—no matter what they do.

We should be ashamed that safety still requires the victim’s namelessness and facelessness. We should be ashamed that courage is punished, not protected.

But we should also say this clearly and without hesitation:

We are proud of her for leaving.

We are proud of her for speaking.

The incident does not expose her character—but our collective failure as a society.

Satabdi Das is an activist, author, teacher. She is the editor of Khader Dhare Ghor (A House By The Canyon: A book on Domestic Violence), has authored Naribadi Chithi O Onyanyo (Feminist Letters and Others) and O-Nandonik Golpo-Sonkolon (The Unaesthetic Stories). Her areas of work are domestic violence, sexual violence and inequalities in school-curricullum. She can be found on Facebook and Twitter.